Discovering Density-Preserving Latent Space Walks in GANs for Semantic Image Transformations

Published in ACM Multimedia, 2021

When I was tackling traversing in the latent space of generator, I was haunted by the identity shift in which you cannot well preserve the identity of the synthesized face images. Then I try to dig into this phenomenon.

Problem Description

Traversing in pre-trained generator has great potential in real life applications, such as image editing, attribute manipulation, and so on. Given a datapoint $z$ in the latent space and a traversing direction $\gamma$, we can change the datapoint $z_0$ along the direction $\gamma_j$ with a stride $\epsilon$ as follows:

\[z(\gamma_j) = z_0 + \epsilon \gamma_j. \tag{1}\]if the resulting datapoint reflects some attributes, for example, adding glasses to a face, change the length of the hair, etc, then we can say the direction is meaningful. How to find these directions remains open problems.

In our model DP-LaSE, we hypothesize that meaningful directions results in maximum variations in the intermediate layer. Let me put it in this way: Imagine a extreme situation where a direction that results in no changes in the intermediate layer, and then this direction cannot be meaningful direction because it’s naive solution. Some works such as $MCR^2$ proposed that dataset can be spaned by several independent subspace that maximizes the coding rate. We believe that meaningful direction should results in largest variation so that the directions can expressed the dataset efficiently.

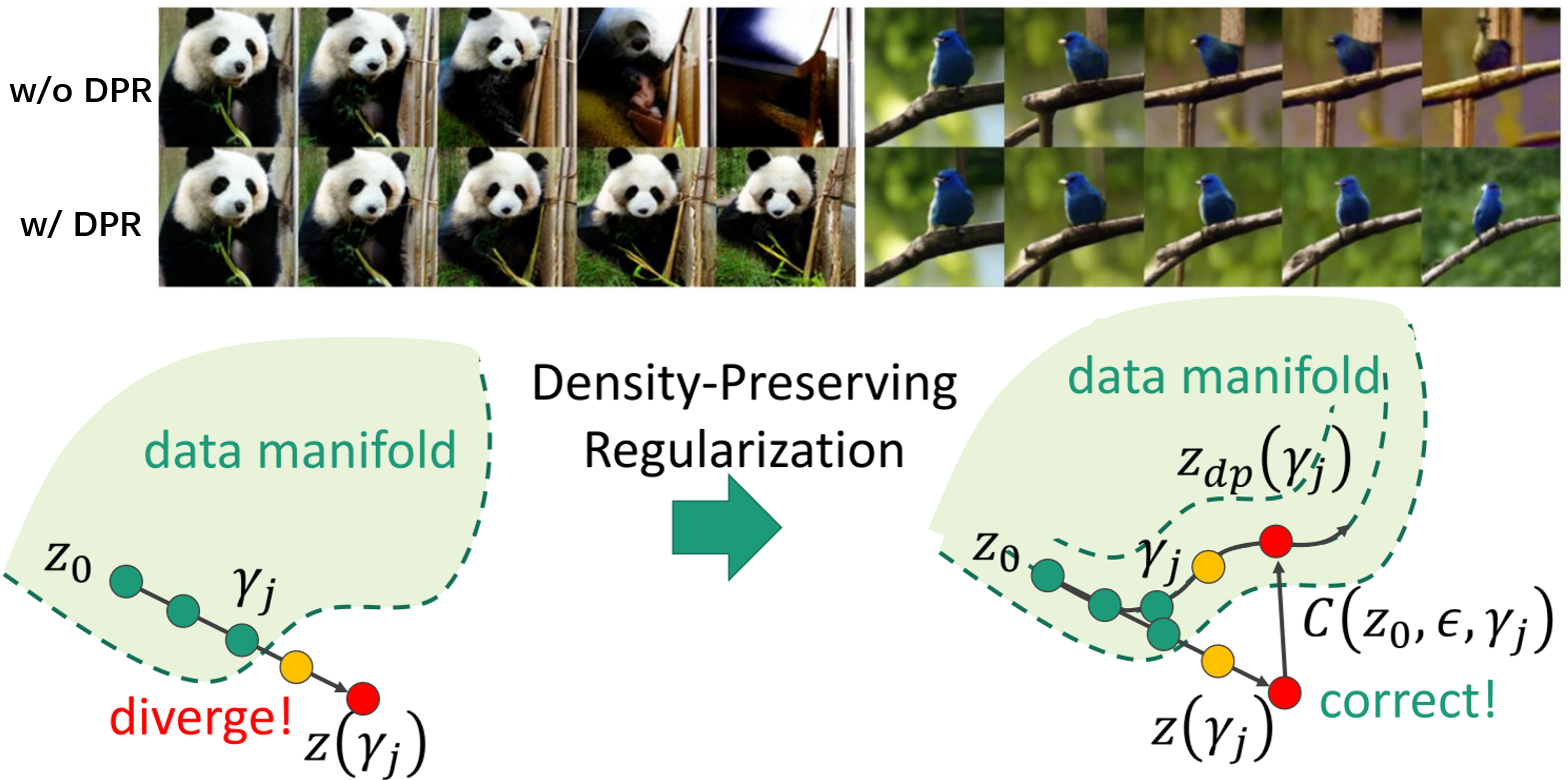

Secondly, once the directions are found, it remains unsolved in how to traverse in the latent sapce. Many research such SeFA and UDUI traverses latent space by linear interpolation. But there is a issue of this — large stride causes interpolation path to diverge from the data manifold. As is shown in Figure 1, increasing stride generally leads the interpolation path to diverge from the data manifold.

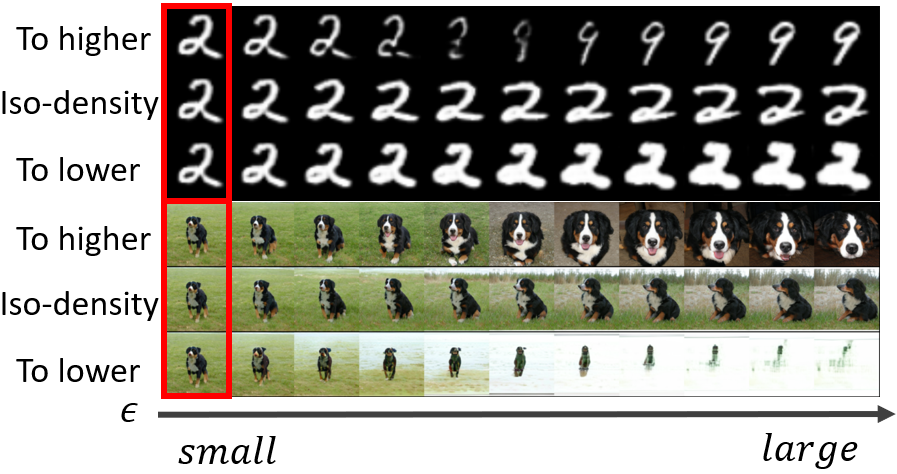

A datapoint that is out of data manifold usually abnormal, because it’s hardly trained in the training phrase since it’s in low probability density area. On the contrary, a datapoint in the high probability density area are frequently trained, so the generation by datapoints there interweaves many attributes even by a small disturbance. We validate the hypothesis in the BigGAN and WGAN, and the results are shown in Figure 2. The pattern can be summarized as follows:

- Moving to higher probability density can cause dramatic change of the image, such as label and background.

- Moving to lower probability density would fade out.

- Moving in the region of same probability density can results in reasonable changes.

Our Implementation

Let’s dive deeper on the implementation.

Density Preserving Traversing

In this part, I am going to talking about Density Preserving Traversing: how to preserve the traversing path in the same density region. For Gaussian prior distribution case, it’s very simple, because we just need to keep the norm the same as the begining point. Therefore, we could write the traversing path for Gaussian prior distribution as follows:

\[z_{dp}(\gamma)=\frac{\|z_0\|}{\|z(\gamma_j)\|}z(\gamma_j). \tag{2}\]For more complex prior distribution, we need to estimate the probability density by sampling it. Therefore, we use a estimation module $F(\cdot)$ to estimate the cumulative density function of prior distribution $p_0$. For simplicity, we assume that the elements of each latent code $z={z^{(1)}, z^{(2)}, \cdots, z^{(d)}}$ are independent and identically distributed, where $d$ denotes the number of dimensions. By definition, the probability density is the derivative of the cumulative distribution function, and we thus have $F(z^{(i)})=Pr(\tau\lt z^{(i)})$ and $p_0(z^{(i)})=F’(z^{i})$, which can be approximated as follows: \(F'(z^{(i)})\approx\frac{F(z^{(i)}+\epsilon) - F(z^{(i)})}{\epsilon}, \tag{3}\)

where we use a very small positive value of $\epsilon$. To ensure that $F$ is monotonically increasing, we define a training loss function $l_{mon}$ as follows: \(l_{mon} = \sum_{i=1}^{d} \max(0, v - F'(z^{(i)})), \tag{4}\)

where $v$ denotes the minimum slope that must be maintained. To approximate the underlying distribution of latent codes, we define a likelihood-based loss function $l_{lik}$ as follows:

\[l_{lik} = \sum_{i=1}^{d} -\log F'(z^{(i)}). \tag{5}\]Benefiting from the density estimation, we formulate density-preserving latent space walks as follows:

\[z_{dp}(\gamma_j) = z_0 + \epsilon \gamma_j + C(z_0, \epsilon, \gamma_j), \tag{6}\]where $C$ denotes a correction module that aims to learn a correction vector. To enforce the density consistency at the start and end points, a loss $l_{den}$ is defined as follows:

\[l_{den} = \sum_{j=1}^{k}\left\| \sum_{i=1}^{d}\log F'(z_0^{(i)}) - \sum_{i=1}^{d}\log F'(z_{dp}^{(i)}(\gamma_j))\right\|^2. \tag{7}\]As will be illustrated in the experiments, $C$ plays an important role when performing a large $\epsilon$-step transformation.

Latent Direction Exploration

Next, we determine the latent directions that give rise to variations in synthesized images in an unsupervised manner. To measure the difference between images in a feature space is typically more effective than that in the image space. We decompose the generator $G$ into two components at an intermediate layer, and the resulting sub-networks are denoted by $G_1$ and $G_2$, respectively. $G_1$ takes a latent vector $z$ as input and produce a set of feature maps $G_1(z)$, which are fed to $G_2$ to synthesize an image. Let $\Gamma = [\gamma_1, \gamma_2, \cdots,\gamma_k ]$ denote a matrix with its columns corresponding to a set of latent directions. We require that moving a latent code in the directions lead to large variations in the intermediate feature space, and define a corresponding loss function $l_{var}$ as follows:

\[l_{var} = \sum_{j=1}^{k}-\|\Delta({z}_0,{\gamma}_j)\|_F^2 +\lambda \sum_{j,h=1}^{k}\texttt{1}_{j \neq h} \cdot \|\Delta({z}_0,{\gamma}_j)^{T}\Delta({z}_0,{\gamma}_h)\|_F^2, \tag{8}\]where the function $\texttt{1}_{j \neq h}$ outputs 1 if $j \neq h$ and 0 otherwise,

\[\Delta({z}_0,{\gamma}_j) = G_1({z}_0) -G_1({z}_{dp}({\gamma}_j)), \tag{9}\]where $\lambda$ is a weighting factor. To encourage $\Gamma$ to associate with different factors of variations, the second term in Eq.(8) serves as a penalty for the similarity of feature changes caused by different latent directions. On the other hand, we also require the latent directions to be orthogonal with each other, and define a regularization loss $l_{reg}$ as follows:

\[l_{reg} = \|\Gamma^{T}\Gamma - I\|_F^2, \tag{10}\]where $I$ denotes the identity matrix. After integrating the above two aspects: density-preserving regularization and latent direction determination, the corresponding optimization problem can be formulated as follows:

\[\min_{F, C, \Gamma} \texttt{E}_{z_0 \sim p_0} [l_{mon} + l_{lik} + l_{den} + l_{var}] + \zeta l_{reg}, \tag{11}\]where $\zeta$ is a weighting factor. The density estimation module $F$, correction module $C$ and latent directions $\Gamma$ are jointly optimized in the proposed framework.

Experiments

We demonstrate some directions in BigGAN and StyleGAN. For dog in BigGAN, we mainly found some directions that cause position change, like left-right, zoom in-out and up-down. For human face in StyleGAN, various directions are found. If the intermediate layer we set to optimize the maximum variation is close to the input, the attribution we found are age, gender, etc. Otherwise, attributes like glasses and bear can be found.

(a) Left-right |  (b) Zoom in - out |  (c) Up - down |

(a) Bear |  (b) Hair |  (d) Gender |  (c) Glasses |

There is more analysis available in our paper, for example:

- The estimation accuracy of our model.

- The disentangle results of our model using subspace propsed in our work.